MY

DREAM

IS NOT

RED

My dream is not red.

In the past 20 years of my life, I have never truly felt happiness.

Today, as I sit here, I want to tell you about my dream.

Performance

OCT. 2024

{\\}() {\\}∆‡!(){\\}

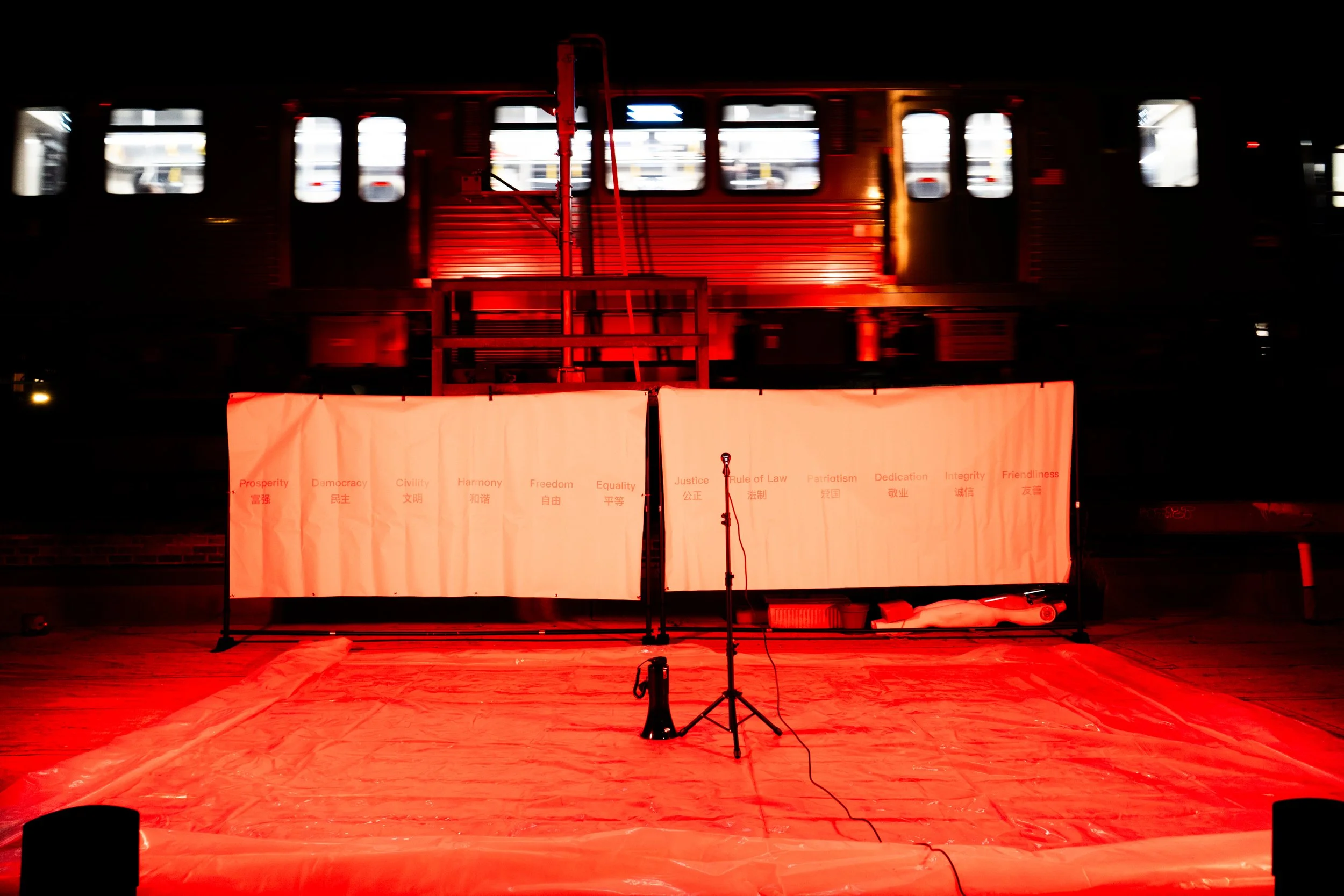

In this performance, the artist stands before the audience holding a protest loudspeaker, speaking aloud their personal dreams—dreams of love, recognition, and freedom.

At first, the voice is clear, intimate, and direct. But soon, a pre-recorded audio of China’s “Core Socialist Values” propaganda begins to blast from the speaker, gradually overpowering the artist’s voice.

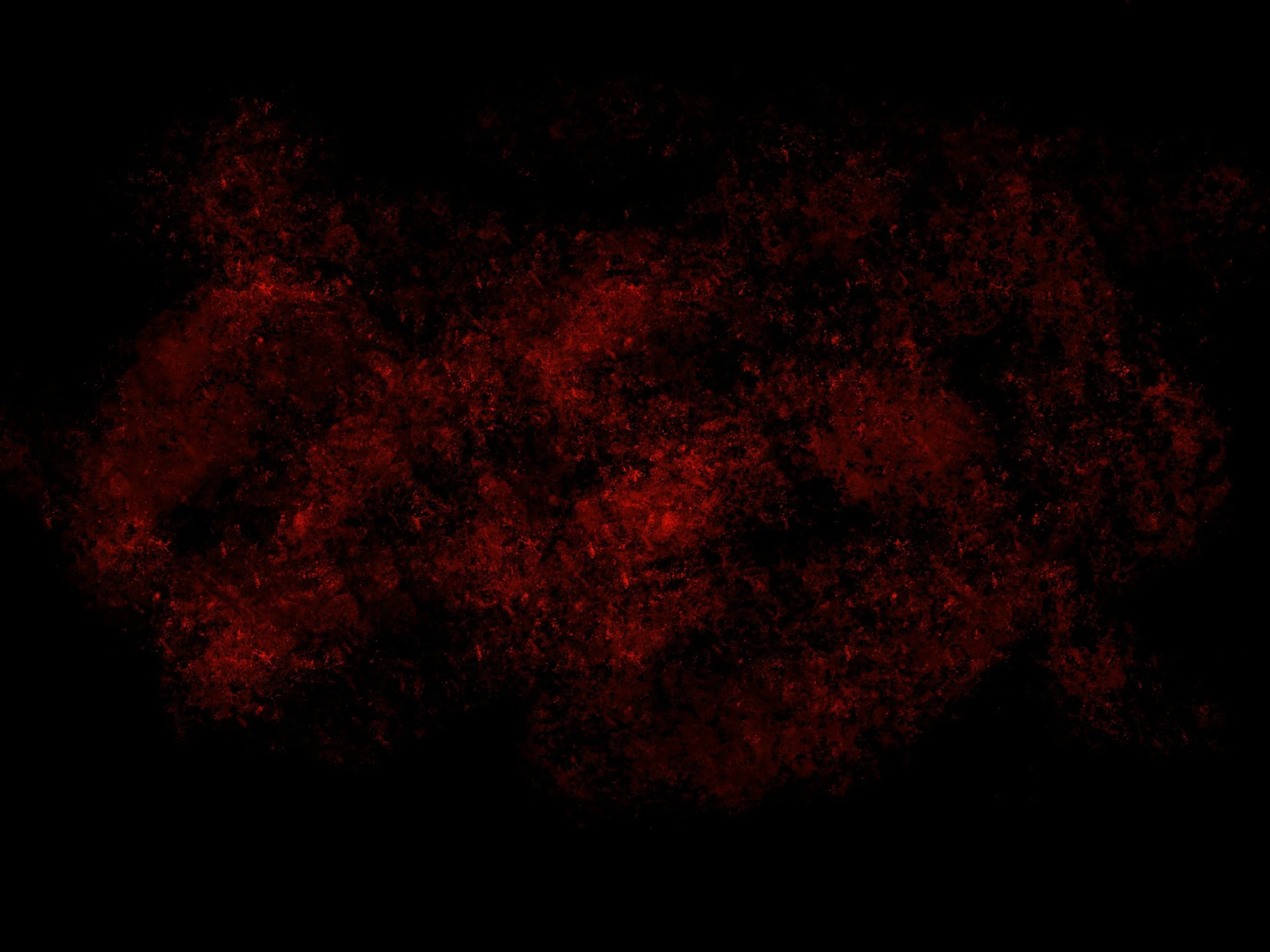

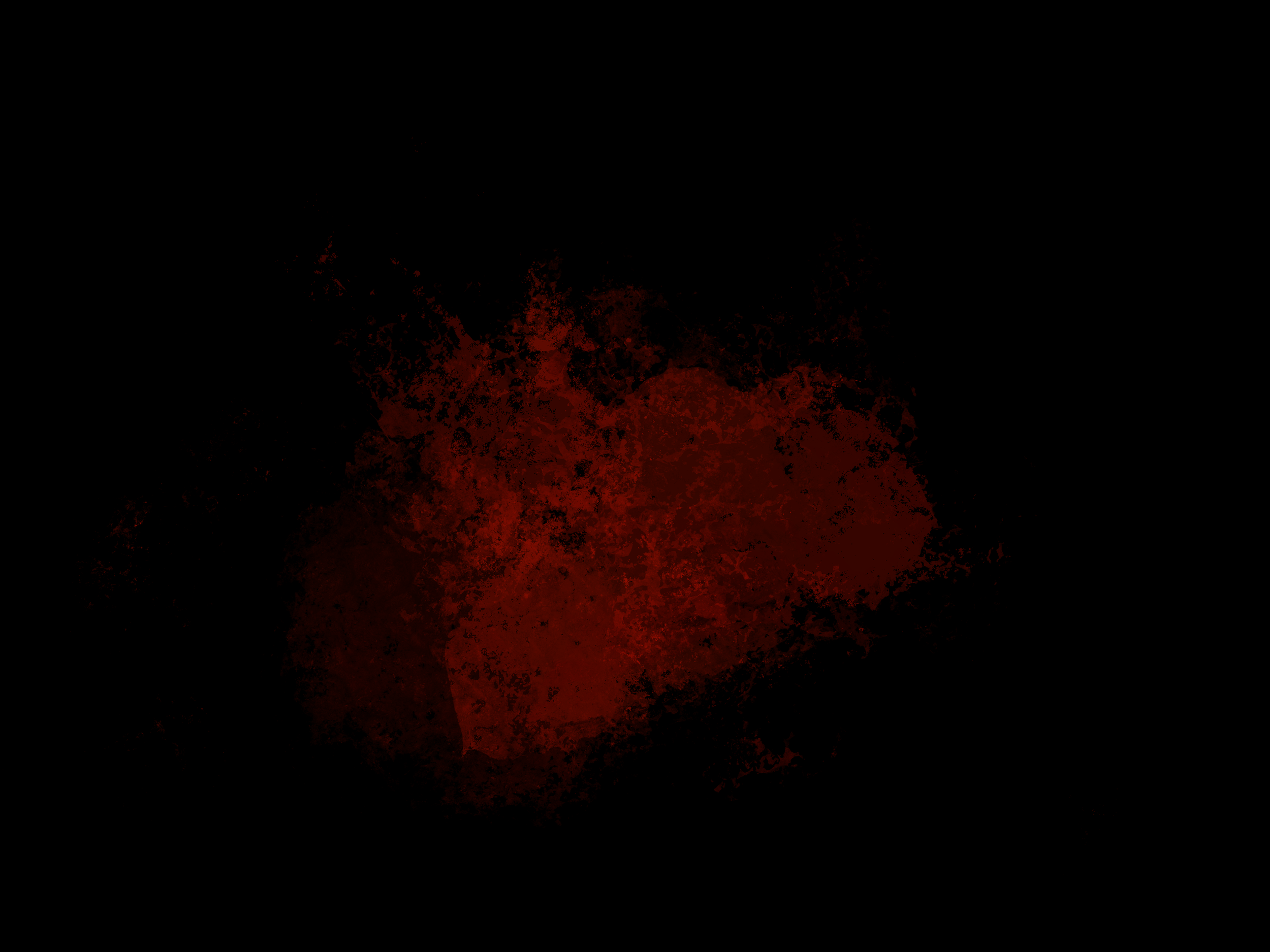

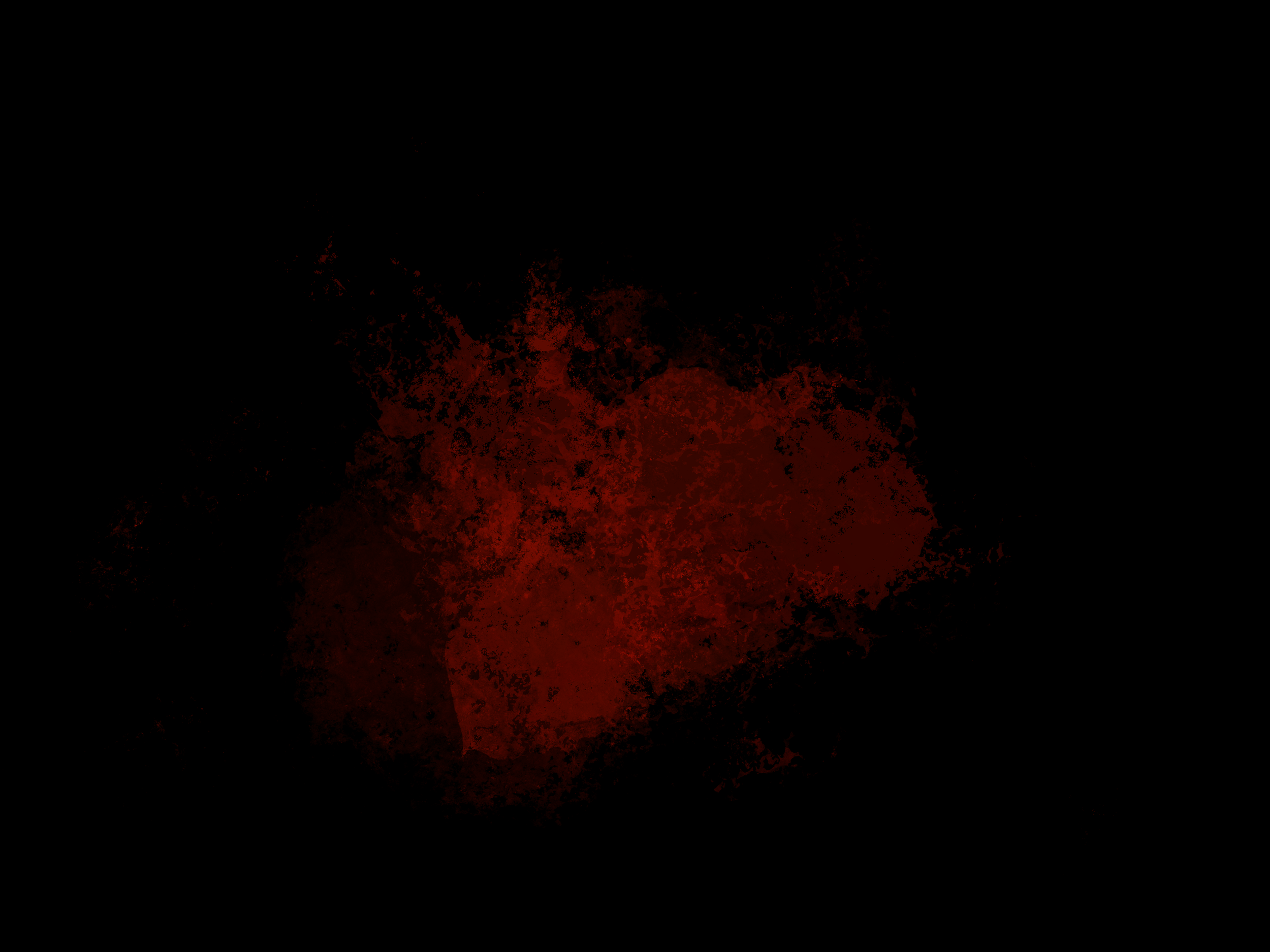

As the artist continues to speak, two buckets of red paint are poured onto their body, staining them and the surrounding backdrop.

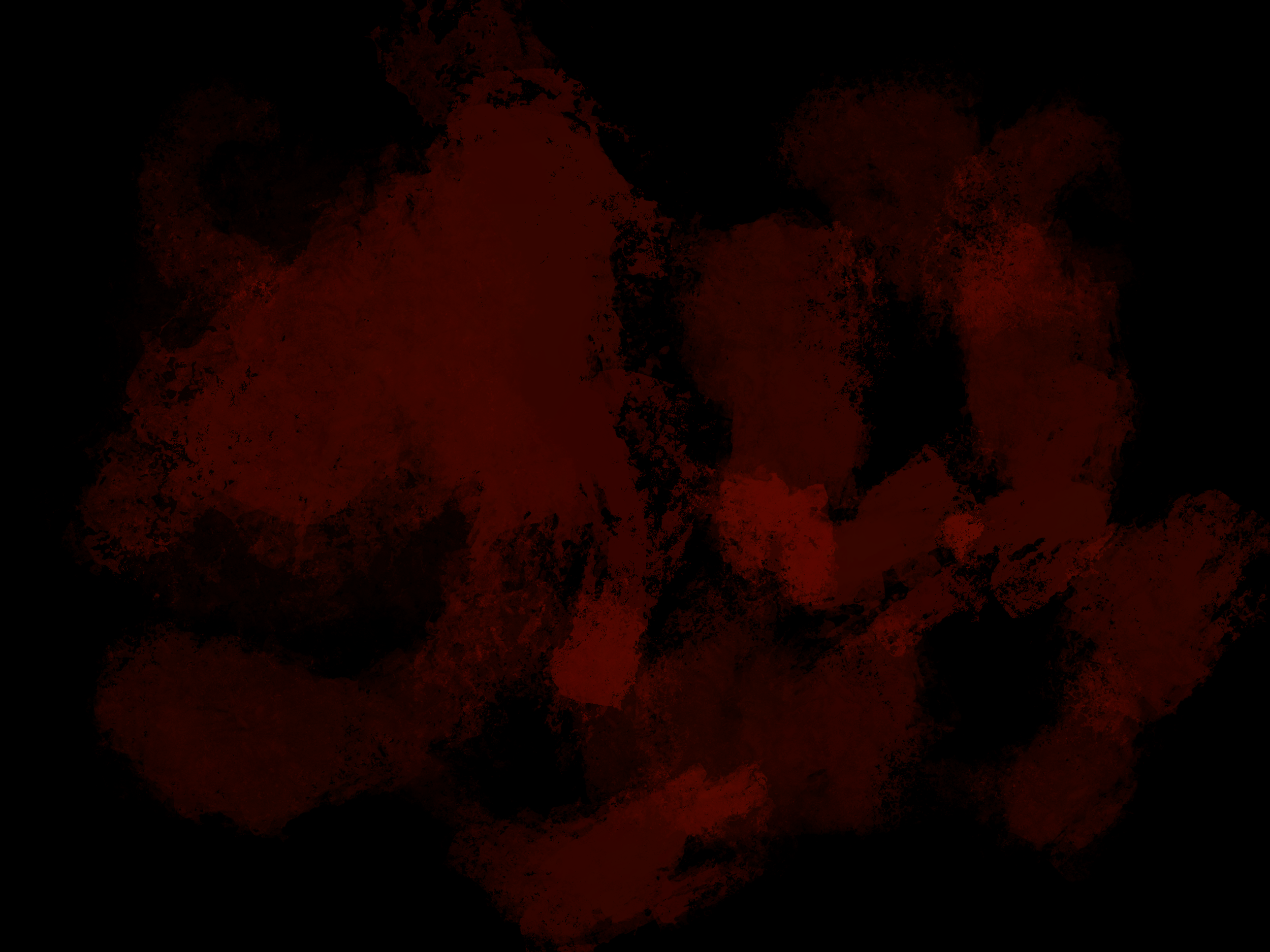

The red is symbolic—of ideology, violence, and erasure. In the final moments, the artist uses their body to smear the red paint across the background images and text, transforming the visual space into a monochrome field of red—an obliteration of individuality beneath a state-imposed dream.

This performance is not only a confession of personal desire, but a confrontation with systems that actively suppress those desires. The red paint in My Dream Is Not Red is not merely symbolic of communism, or of the Chinese flag—it is the color of control, the color of slogans repeated until they drown out human voices.

The act of continuing to speak—mouth moving even as the speaker emits something else—is central to this work. It becomes a visual metaphor for life under authoritarian regimes: where the body performs compliance, but the soul refuses silence. The megaphone, a tool of protest, is turned into a weapon of erasure; the very device that should amplify is hijacked by propaganda.

The body in this work is both subject and surface. It receives the violence of the state—sticky, staining, irrevocable—but it also resists through presence, insistence, and vulnerability. The artist does not dramatize resistance in the traditional sense; instead, they stage the quiet futility of being heard in a system that speaks louder than you ever can.

The photographs in the background—initially unnoticed—reveal their significance only in the moment of destruction. This temporal delay mirrors how political violence often works: what feels like background becomes center stage when it’s already too late.

In a world where ideology colors everything, even our dreams, My Dream Is Not Red asks a fundamental question:

What does it take to reclaim your voice when the very tools of speech are no longer yours?

A Final Note

This was the first time I created a politically charged work about China on American soil—specifically, in Chicago, a city layered with its own histories of migration, protest, and racial complexity. To speak about censorship, authoritarianism, and queer desire from the standpoint of a Chinese body abroad is not neutral—it is inherently fraught.

I was not only confronting the silencing mechanisms of my homeland, but also negotiating how that silence is received, interpreted, or even consumed in a Western art context that often exoticizes “resistance” from the Global South.

To stand in front of a mostly non-Chinese audience and speak about dreams that are illegal or invisible back home—while wrapped in another country’s liberal promise—felt at once liberating and deeply disorienting.

Who gets to speak about oppression? Who gets believed? Who gets protected when they do?

This performance was not only about being silenced.

It was about the fragile permission to speak, and the uneasy privilege of being heard—only after leaving everything behind.

Live performance video abbreviated version (6Min.)